Saturday July 11, 2020 — Brooklyn, New York

I mentioned in a sidenote in one of my previous entries that I wasn’t certain that humans are the only species that are “higher-order toolsmiths” — that is, making tools that are used solely to make other tools. Specifically, New Caledonian crows are a possible candidate for a species that does, as are some primate species.Primate tool use is interesting, since tool use capabilities seem to vary a lot by species, but not in a way completely explained by some species being clearly better at using tools and some clearly worse — there seems to be something more complicated going on, where different species are predisposed to different types of tool use and being good at different problems. I didn’t include anything concrete about crow tool use in that post, primarily because I wasn’t able to find a copy of the papers that seemed most relevant when I was writing it. But I emailed one of the authors of Tool manufacture by New Caledonian crows: chipping away at human uniqueness, and they kindly got back to me with a PDF of that paper, as well as a chapter with a more up-to-date overview of animal tool use in general (Cognitive Insights From Tool Use in Nonhuman Animals), which included an excellent section on New Caledonian crows.

A clever cutie holding a hook tool

A clever cutie holding a hook tool

Image credit: Cornell University

Reading more about the subject has made me more confident in my assertion that humans are the only higher-order toolsmiths, but it also revealed a bunch of interesting facts about animal tool use that I think are worth sharing.

New Caledonian crows are a species of crow that is native to New Caledonia, a French colony just outside of Polynesia. They are extremely capable tool-users, and appear to be so by nature, being able to develop tool-use capabilities in captivity, as well as showing evidence of learning more advanced methods of tool use socially. New Caledonian crows have several claims to being the most advanced tool-users other than humans, but one of the most interesting to me is that they’re the only species other than humans to have invented hooksAs of 1996 — it’s possible that there has been new evidence or new evolutions in tool use since then. — something that requires a quite complex manufacturing process.  Hook construction

Hook construction

Image credit: Elisabetta Visalberghi et al. In addition to both hooked and non-hooked stick tools, New Caledonian crows use flexible tools made from the leaves of pandanus trees. There are several distinct kinds of pandanus leaf tools that crows make — wide tools, narrow tools, and stepped tools (offering the advantages of both the wide and narrow tools, but significantly more complex to manufacture). Interestingly, different crows exhibit personal preference with regards to which type of tools to use, with mated pairs of birds sometimes exhibiting different preferences.

While captive New Caledonian crows exhibit tool use,In general, captive animals show more of a propensity for tool use than wild animals — a term referred to a “captivity bias” there is also some evidence that tool use is a socially-learned behaviour — we can see that pandanus leaf tools are generally similar within a given site, but exhibit differences at different sites. Since New Caledonia is small enough that one would not expect significant genetic variation within the island, it’s likely that these differences are learned, rather than genetic. In addition, young New Caledonian crows stay in their parents’ home ranges for the first year of their lives, often in very close quarters with their parents as they forage — Visalberghi et al. note:

Mated pairs are extremely tolerant of their offspring […] For example, they tolerate juveniles at close quarters when using tools, even when juveniles sometimes “steal” their parents’ extracted food and tools.

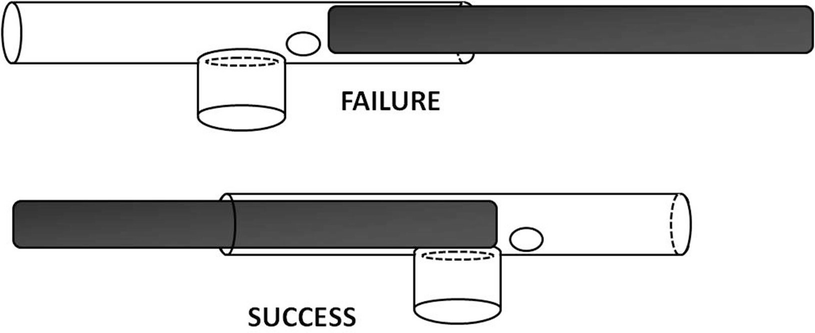

One final interesting tidbit from this research is that, while it’s easy for humans to be haughty about our superior tool-use capabilities, when they’re actually put to the test, we sometimes don’t do so well — one common experiment testing both tool-use and cognition is the “tube-trap problem,” wherein a tube has a reward in it, only reachable with a tool, but there is a small hole in the bottom of the tube that will render the reward inaccessible if it is pushed in.  The tube-trap problem

The tube-trap problem

Image credit: Luca Antonio Marino Once an individual has learned how to avoid the trap, a second variation is to turn the trap upside down (rendering it useless), and see if the individual continues to (unnecessarily) avoid the trap. After explaining the crows continue to avoid the ineffective trap, indicating that they haven’t learned how the problem fundamentally works, the chapter notes:

In fact, adult humans consistently inserted the stick into the end of the tube farthest from the reward and avoided the tube side with the trap also when it was above the tube and, thus, ineffective.

So maybe we shouldn’t be too quick to judge.