Respecting Complexity

Tuesday October 26, 2021 — Upper Jay, New York

I’ve been reading a lot recently about neurochemistry.Specifically, I’ve been reading about 5-HT metabolism, and various drug interactions there. Hopefully I’ll write up a summary at some point. One of the most important takeaways from this so far has been respecting complexity: the human body is a incredibly complex system — humanity as a whole only has a very rudimentary understanding of how our bodies work, and I personally only know an infinitesimally small amount of that. I think that this is broadly true, and it’s good to remember this when trying to understand any sort of complex system.

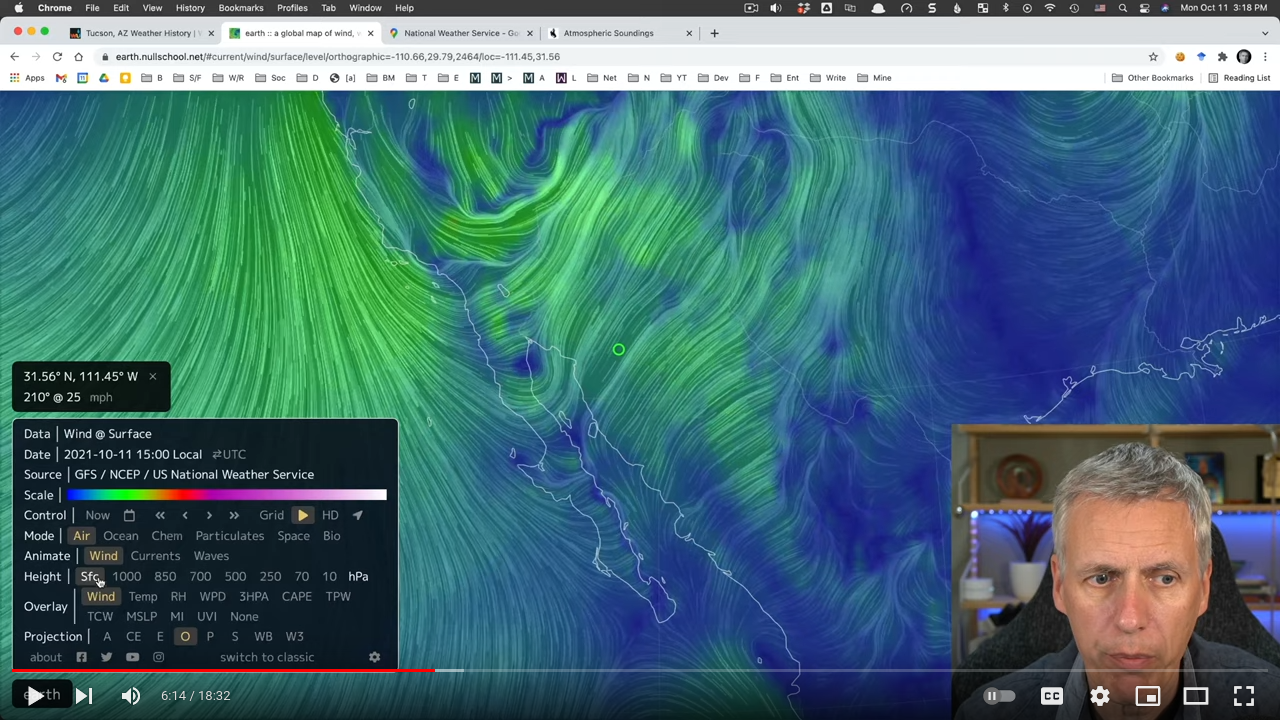

Another example of this I recently came across is Mick West’s lovely explanation of how to analyze historical weather data. There are lots of seemingly “simple” things that people do that are actually subtly wrong for any one of around half a dozen different reasons. It’s essentially impossible to know the exact wind speed at a arbitrary point in space and time with 100% certainty, and the only people who claim to are people who don’t understand the complexities involved.

Another example of this I recently came across is Mick West’s lovely explanation of how to analyze historical weather data. There are lots of seemingly “simple” things that people do that are actually subtly wrong for any one of around half a dozen different reasons. It’s essentially impossible to know the exact wind speed at a arbitrary point in space and time with 100% certainty, and the only people who claim to are people who don’t understand the complexities involved.

One of the insidious things about complex systems like this is that you can often do the simple, incorrect thing, and still get the “correct” answer, just because there were several things you got incorrect that happened to stack up in a way that makes things correct. Dan Luu wrote about this sort of thing recently:

Back in college, there was one group of folks that, for whatever reason, stood out to me as people who really didn’t understand the class material. When they talked, they said things that didn’t make any sense, they were struggling in the classes and barely passing, etc. I don’t remember any direct interactions but, one day, a friend of mine who also knew them remarked to me, “did you know [that group] thinks you’re really dumb?”. I found that really delightful and asked why. It turned out the reason was that I asked really stupid sounding questions.

In particular, it’s often the case that there’s a seemingly obvious but actually incorrect reason something is true, a slightly less obvious reason the thing seems untrue, and then a subtle and complex reason that the thing is actually true. I would regularly figure out that the seemingly obvious reason was wrong and then ask a question to try to understand the subtler reason, which sounded stupid to someone who thought the seemingly obvious reason was correct or thought that the refutation to the obvious but incorrect reason meant that the thing was untrue.

In general, I think one of the most common errors in understanding that people end up with is thinking that things are monocausal. Almost nothing is monocausal, and trying to understand complex, deeply interdependent systems is a good way of keeping yourself humble and able to remember that.