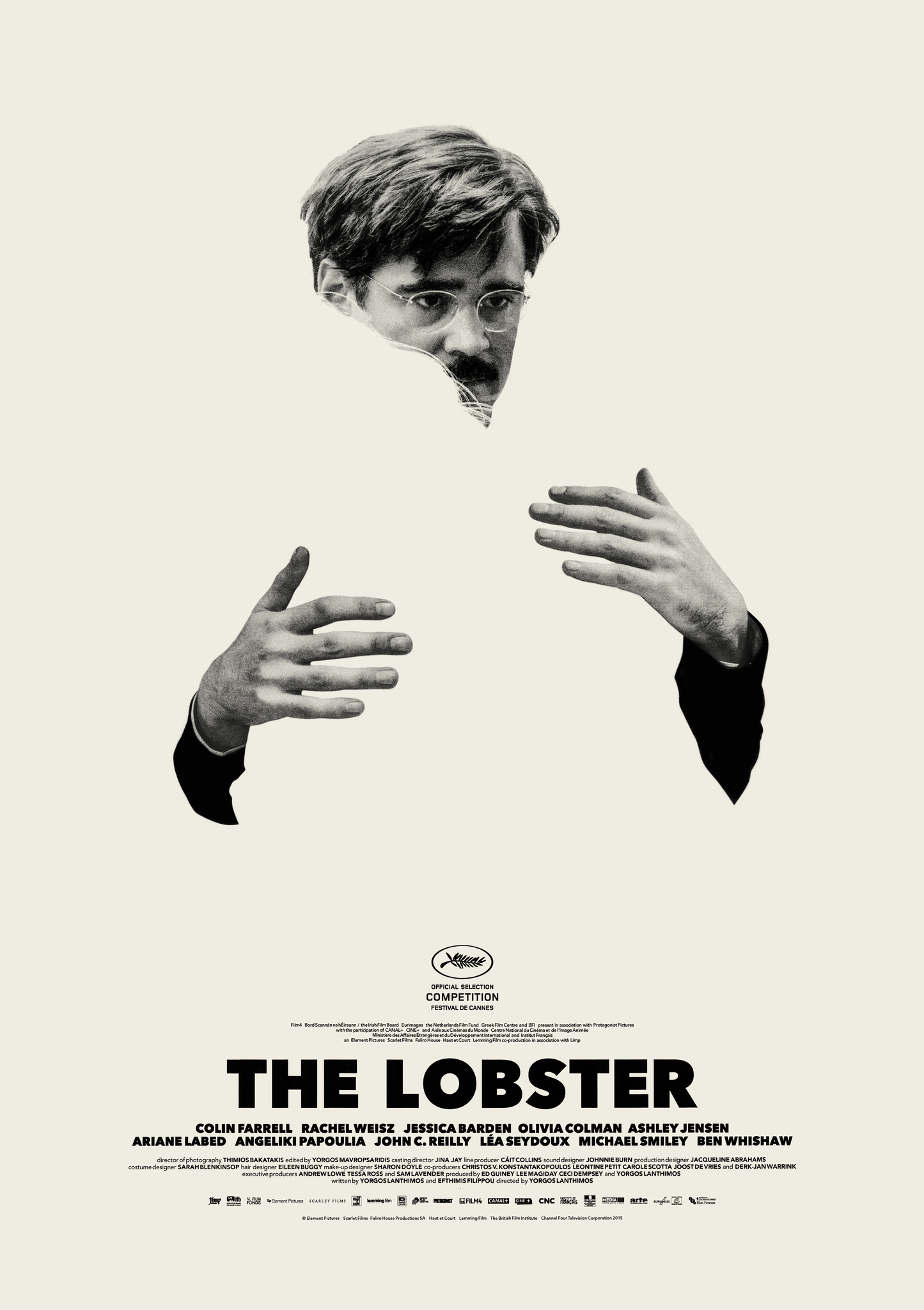

The Lobster (2015)

Monday September 6, 2021 — San Francisco, California

I watched The Lobster again last night — it’s one of my favorite movies. This is an explanation of what I see in the film, and as such it will simultaneously not make sense and spoil it if you haven’t seen if before — if you haven’t seen it and might want to, I recommend closing this tab :)

The Lobster opens up as a sort of commentary on the absurdism of modern relationships — the first act is about the superficiality with which people choose their partners. But rather than making the mistake of attributing that to personal moral failing, the movie is sure to show that people see relationships as superficially as they do because of the structure of the society that they’re embedded within. People speak of having a Defining Characteristic, and everyone understands what they mean — it would be weird for someone to think that they didn’t have a Defining Characteristic, and once you’ve decided on your Defining Characteristic, it would be weird (unthinkable, even) to not pick your partner based on it. We might blame the characters for being too conformist, but our own society (and perhaps even every possible society) is made out of conformity as well.

David doesn’t choose to act with conformity throughout the film, though — he eventually runs off with the Loners, and for a moment it seems as though he may have escaped — as the leader of the Loners tells him, “You can stay with us for as long as you like. You can be a loner until the day you die, there is no time limit.” Immediately after that, however, David finds out that the Loners are a sort of dystopia in exactly the same way that the Hotel is — they have the same way of thinking about relationships, it’s only the polarity that’s reversed. This is where The Lobster makes its real point — that in order to escape the problems of his society, it’s not enough to keep your conceptual framework the same and just reverse the parts that are bad — you instead need to fundamentally change the framework through which you see the world.

Throughout the film, David doesn’t learn this lesson — when the narrator is blinded, he briefly considers teaching her German so that they would have something in common, as though he’s unaware of the fact they they’ve developed their own gestural language — the only thing he can find to make them alike is to blind himself. Perhaps, though, you can learn the lesson, even if David can’t quite see it.